The Last Dance

The time is just past midnight on Sunday 23 November 2025. I am trying to wind down, but the adrenaline of the week still hums in the background. On Wednesday, I completed my final examination of medical school; a viva voce for general surgery.

For the students in the year below who will face this hurdle next year: this one is for you. My friend Nicholas and I have estimated that the reading material for this exam covers roughly a thousand pages of notes, handouts, and textbook chapters. I have attached an image of a list with most of the topics that need to be covered in some depth. It is a Herculean volume of work for a twenty-minute conversation. The format is simple but high-stakes: twenty minutes, two surgeons, and usually two distinct cases of about 10 minutes each, but this may differ depending on your examiners. You might get lucky with "bread and butter" topics e.g., acute appendicitis or an approach to GI bleeding, or you might get something a little bit rogue. For better or for worse, I think can can fairly say that I fell into the latter category.

The Waiting Room

My examination was scheduled for 14h00 in the afternoon on the 19th of November. I spent the morning trying going through some of the basics and the rather more complicated scoring systems or classifications that were reasonably likely to come up e.g., Tokyo guidelines for cholangitis, the Forrest classification for bleeding ulcers, TI-RADS and BI-RADS ultrasound scores, CEAP and Rutherford classifications in vascular surgery et cetera - there really are too many.

At about 13h35 I got dressed and headed up to the Surgery department. We were allocated to different rooms and sent to wait outside them. I was stationed outside the office of the Head of the Breast and Endocrine Surgery at Tygerberg Hospital. She is has become known for particularly difficult and quite specialised viva voce examinations which the group in June really struggled with. A few minutes before my slot, the candidate before me walked out; the look on her face didn't do much to ease my nerves. To make matters worse, I caught a glimpse of the second examiner; a registrar (or perhaps a consultant now) I’d met two years ago and really struggled to build rapport with. It didn't bode well, but I maintain that if you're not nervous before these sorts of things then you probably don't care enough.

When the bell rang, I was welcomed in. The first question wasn't medical; they asked where I was going next year. When I mentioned Pietermaritzburg, the senior registrar smiled. "That’s Dr. X's old hunting ground," he said, referring to the other examiner. And just like that, the scenario began.

Case One: The Acute Abdomen

The Scenario: You're on call for surgery at Edendale hospital and one of the consultants, Mr. Y has sent you down to the emergency room to see a 38-year-old male acute abdominal pain. He has no past medical or surgical history, and has never been to hospital before. Describe your approach to this patient.

The Initial Approach: It is reasonable to start with ABC assessment to identify whether or not the patient is in extremis. I said I'd start by greeting the patient and assessing his response to my salutation.

- Airway/Breathing: I established he was talking normally, his trachea was central and that he had normal breath sounds bilaterally.

- Circulation: I asked for the vital signs: BP 80/40 mmHg, HR 140 bpm, Temp 37.6°C, RR 18.

- Interpretation: This patient is in shock.

- Action: Two large-bore IV lines, resuscitation with isotonic crystalloids. When asked which specific crystalloid I would use I said we can use Lactated Ringer's solution, starting with a 1-Litre bolus.

- We should also collect blood for some basic investigations while obtaining IV access: a venous blood gas, an EDTA tube (purple) for a full blood count, and a serum separator tube (yellow), and then take a full history before deciding which investigations to order.

The History and Physical Examination:

History of presenting complaint: I asked the standard SOCRATES questions. The pain started suddenly at 08:00 while smoking and sitting on the couch at home. It is a constant 8/10 intensity, and it is localised to the epigastric area and not radiating, and unresponsive to his usual pain medication and he has not noticed any major exacerbating or relieving factors.

I enquired what was meant by 'usual pain medication' and they said he frequently takes myprodol and ibuprofen (over the counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). I then enquired specifically for other risk factors for peptic ulcers. Apart from NSAID use and smoking, he was also a big drinker and used 'tik' (methamphetamine). I also asked if there was a recent alcohol binge and the examiners said that he had had a lot to dink over the weekend.

This history was strongly suggesting a perforated peptic ulcer or possibly an acute pancreatitis. I asked what was remarkable about the general and abdominal examination, and they said that tenderness in the epigastric area and that he was peritonitis... interestingly I don't recall them saying it had 'board-like' rigidity. Systems enquiry was relatively unremarkable, I think they said he may have vomited once.

At this point I said that I think he has a perforated peptic ulcer, and although I could ask more questions to try and establish prior symptoms of peptic ulcer disease or other associated symptoms, I'd like to get an erect chest X-ray ASAP since he is in extremis. Before getting to that, they wanted me to give a differential diagnosis...

Differential Diagnosis:

- Perforated Peptic Ulcer: The very sudden onset of pain and the presence of numerous risk factors make this the most likely diagnosis.

- Acute Pancreatitis: The alcohol binge makes this essential to exclude. We should send blood for lipase and we are looking for an elevation greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal. I was asked to list causes of acute pancreatitis, so I started with the most common: alcohol binge and gallstones. Then moved on to some of the others: hypercalcaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, steroids, trauma, mumps, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Unfortunately I betrayed the medical student alliance and neglected to mention scorpion sting.

- Acute Mesenteric Ischaemia: They wanted another one, so I came up with acute mesenteric ischaemia. Although I though this was a bit of a of a long shot in a 38-year-old, it could also give the sudden onset pain and would fit with the metabolic acidosis and lactate of 6 mmol/L which they had given me when I said I would do a venous blood gas. I suggested that, given his drinking history, he could have alcohol-induced atrial fibrillation i.e., "Holiday Heart Syndrome", and and an embolism could have occluded the superior mesenteric artery. I said I would examine for an irregularly, irregular pulse, and conduct an electrocardiogram. I didn't bother mentioning a pulse deficit or the absence of a-waves on the jugular venous pressure; I figured this might not interest surgeons. They seemed to like the logic, even though I am pretty sure most people who develop AF after a binge go back into sinus rhythm within a couple of days and you probably need an arrhythmia for a significantly longer period to be at risk of emboli.

Investigations: The main one is an erect chest X-ray, looking for free air under the diaphragm. I also said you can look for Rigler's sign if a supine abdominal X-ray had been done. They showed me the film, and it was an obvious pneumoperitoneum, so this confirmed perforation of a hollow viscus, likely a perforated peptic ulcer. Then they asked me what the appropriate management would be.

Management:

- General measures: Give opiate analgesia and a high dose proton pump inhibitor (e.g. 80mg pantoprazole) intravenously. Insert a nasogastric tube.

- Theatre: Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI) and Laparotomy.

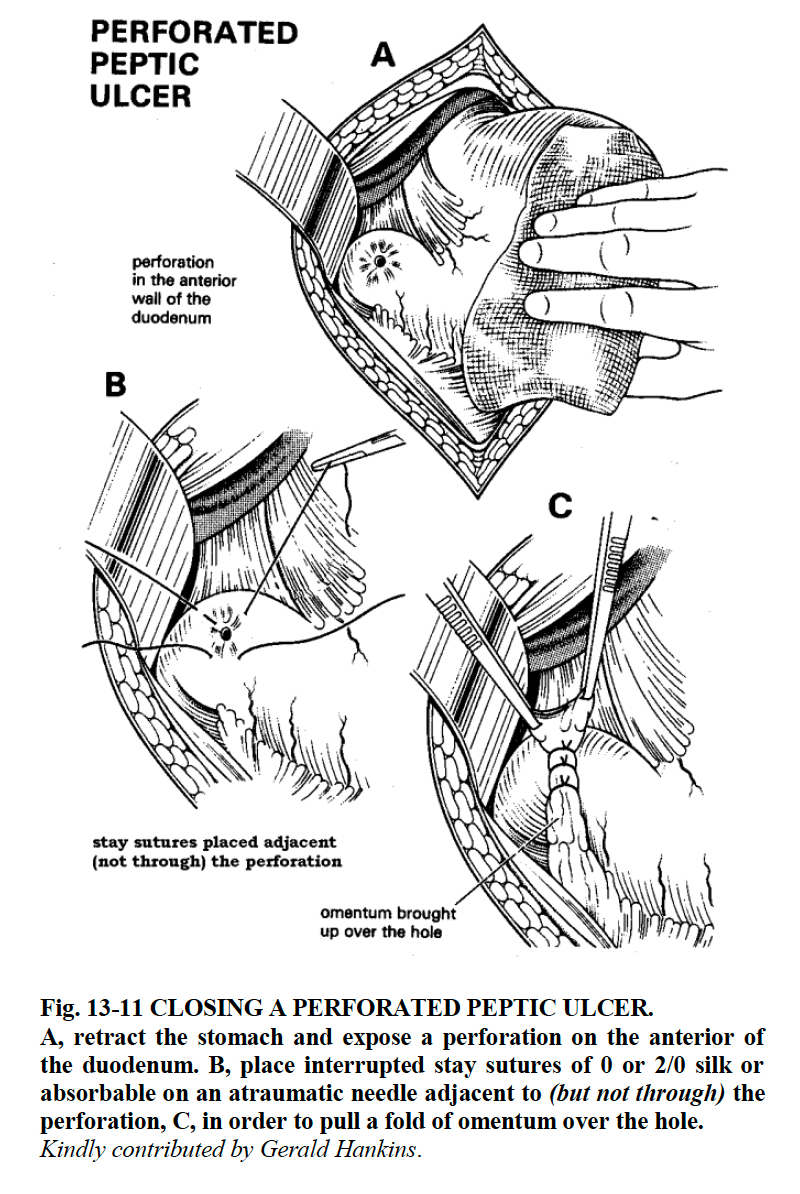

- Repair: Omentopexy (Graham Steele procedure) using the omentum to plug the perforation. If it is a gastric ulcer you should also take a biopsy to rule out malignancy.

- Post-Op: H. pylori eradication triple therapy (PPI + Amoxicillin + Metronidazole/Clarithromycin).

Curveballs: I was then asked for causes of a non-healing ulcer. I said the feared reason is malignancy, and then others are immunosuppression which may be from HIV/AIDS or diabetes or immunosuppressive drugs, non-adherence to H. pylori eradication therapy. They asked if a patient comes to you in primary care with a scope report saying that they have a peptic ulcer, which of them will you not give H. pylori eradication? This is a bit of a trick question because you should eradicate them all. I asked if they had already been eradicated and if not then I would certainly give them the drugs and follow up. I said this was the right course of action because most ulcers are caused by H. pylori as demonstrated by Marshall and Warren who won the 2005 Nobel Prize for their work.

I also mentioned Zollinger-Ellison syndrome as a cause for non-healing ulcers, and they jumped at that and made me explain it. So I said it's due to a gastrinoma (a tumour producing gastrin) which stimulates excessive acid production and secretion from the gastric parietal cells. They then asked where the gastrinoma is. Fortunately I knew that it is typically in the duodenum or the pancreas; many students assume it is in the stomach, but it isn't.

Case Two: The Parathyroid Pivot

"You mentioned that hypercalcaemia can cause acute pancreatitis. Let's talk about hypercalcaemia". Scenario: A patient in their thirties is incidentally found to have a raised serum calcium. What are possible causes for this?

The main differentials I gave were hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. I said specifically primary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism. The examiner said secondary is also possible... I thought once that happens then it's tertiary, but I didn't argue. The hypercalcaemia in malignancy may be a paraneoplastic syndrome in where the tumour produces PTH related peptide, or it may be due to osteolytic bone involvement. Then I said it could be familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH) or Vitamin D toxicity. I unfortunately neglected to mention granulomatous diseases where there is ectopic production of 1-alpha-hydroxylase.

I was then asked about subsequent workup for this patient. Which I described perhaps in the wrong order in that I described imaging first, but I justified it by saying that if there was no suspicion of malignancy on clinical examination, then a parathyroid adenoma is the most likely cause - and then obviously we need to find which of the parathyroids is implicated. You can do a Sestamibi scan; I just said a nuclear medicine scan as the name had slipped my mind in the moment. Ultrasound can also identify the enlarged gland. High PTH with the high serum Calcium usually indicates primary hyperparathyroidism, although strictly you still have to rule out FHH with a 24h urinary calcium measurement. Serum urea and electrolytes should be done to assess the renal function. Additionally, the serum and urinary phosphate should be done; in primary which they were describing there is low serum phosphate and high renal loss of phosphate. The examiners were happy to move on after this.

Intra-operative Confirmation: The examiner asked, "How do you know you've excised the parathyroid?" I said you take them out under direct vision and I initially described the anatomical relations, but they pressed me again asking how could I be sure? So I said that you could send the specimen to the pathologist. She asked what the pathologist would see, and I managed to pull out "chief cells" from somewhere deep in the preclinical memory banks which earned a nod of approval. An alternative answer to this question which I think is what they were initially looking for, is that you can do intra-operative PTH monitoring because PTH has a very short half-life and the plasma level drops rapidly once the adenoma is removed.

Post-Thyroidectomy/Parathyroidectomy Complications: I was then asked what I have to worry about in the post-operative period. I said I had two main things that I would be worried about. Firstly, haematoma compressing the trachea; an airway emergency necessitating immediate relief. This is usually considered to be a complication of thyroidectomy, but I thought it was still a reasonable answer given the dissection of the neck to reach the parathyroids. Secondly I said hypocalcaemia, as the remaining (non-adenomatous I guess you could say) parathyroid have been suppressed. This was what they wanted to talk about, and they asked me what the signs will be.

I mentioned general malaise, circumoral numbness or paraesthesia, tetany, and the classic Chvostek and Trousseau sign which I was asked to describe.

- Chvostek sign: Tapping the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve causes facial twitching.

- Trousseau sign: You inflate a blood pressure cuff over the brachial artery to just above the systolic pressure, classically for 3 minutes, and this precipitates carpopedal spasm. The patient develops the "main d'accoucheur" posture which is French for Hand of the Obstetrician (I was specifically asked about this so it is worth remembering and fortunate that I knew it)

Case Three: The Rapid Fire

With a couple of minutes remaining, they handed me a photo of a back with a large, fungating, bleeding tumour surrounded by seborrheic keratoses and asked me for a differential diagnosis.

I hadn't studied much pathology of the skin or soft tissues, but I pretty much gave a differential diagnosis of any skin tumours that came to mind: squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, melanoma, or keratocanthoma. I said it could also be a metastasis, and the surrounding seborrheic keratoses could be indicative of the leser-trelat sign of metastatic gastric or GI cancer. I was then asked how would I get a diagnosis, and obviously you need a biopsy and they wanted to know which kind of biopsy I would do. I said I would do an incisional biopsy, mainly because the tumour was too big to excise all of it, and they were happy with this, but they also asked for an alternative. I was unsure, but I said that you can do a punch biopsy as well; I was thinking about what other types of biopsies could give you an idea of the Breslow depth if it was a melanoma. They said that the report has come back and that it is a melanoma, and then they asked me what are the 4 main clinical subtypes of melanoma. I managed to remember superficial spreading (the most common type), acral melanoma which includes subungual (which Bob Marley had) and nodular melanoma. And then the last one is lentigo maligna melanoma which I struggled to recall, but described its typical location on the face.

And then the bell rang and the time was up.

Reflection

One of the examiners opened the door for me and as I was leaving asked if I want to be a surgeon. I sort of messed up here and gave a non-committal "Maybe." If I've learnt anything from senior Stellenbosch doctors, especially surgeons, they seem to value certainty and conviction (at least much more than I do). I should have just said yes.

Nevertheless, in retrospect, this was one of my best performances in a medical school assessment, so it was nice to end on. Although some of the questions were difficult, I think the examiners were fair and some basic science and foundational understanding went a long way.

I may in future write up a guide to approaching this exam and surgery in general in the final year, but that is it for now.